‘Play ball!’— the perennial cry at the start of the game in the American baseball season. Why an article about American baseball in a magazine distributed in southern England* you may ask? Well, although baseball is arguably the all-American sport today, this wasn’t always so, for baseball actually developed here in southern England, from at least 1700!

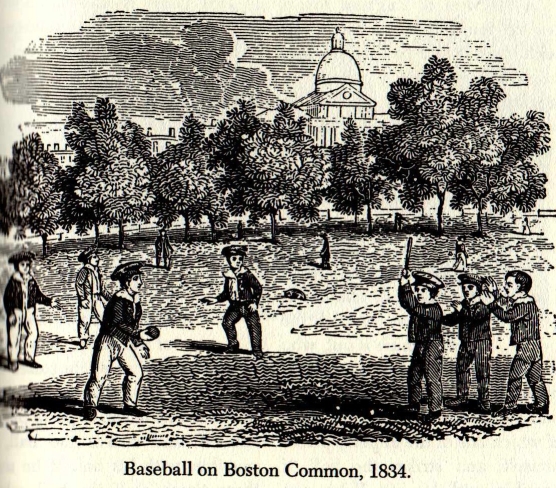

Everyone, it seems, associates baseball with America. This is not unreasonable, for baseball was unquestionably developed, as it is played today, in the USA; and for a great part of the 20th century, and indeed starting in the late 19th century, baseball was played almost exclusively, at least as a professional sport, in America — and, in fact, up through the 1920s there were only 16 Major League teams. Further, St Louis, Mo was the farthest west and Washington DC the farthest south that Major League baseball was played! After WWII baseball’s popularity spread and although it does not enjoy the universality of soccer football it is played throughout the world – all over North America, throughout the countries of the Caribbean ‘rim’, Japan, Australia, South Africa and throughout Europe.

There are many myths about the origin of baseball. The classic one, and one ‘still cherished’ by many Americans is that the game was ‘invented’ by the American Civil War General Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York in 1839. This myth was perpetuated in books and articles throughout the 20th century. But as early as the 1940s, by which time professional baseball in the USA had been in full swing for more than six decades, the Chief Librarian of the New York Public Library, Robert W. Henderson, had begun to question and to delve into the true origins of the game.

There are many myths about the origin of baseball. The classic one, and one ‘still cherished’ by many Americans is that the game was ‘invented’ by the American Civil War General Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York in 1839. This myth was perpetuated in books and articles throughout the 20th century. But as early as the 1940s, by which time professional baseball in the USA had been in full swing for more than six decades, the Chief Librarian of the New York Public Library, Robert W. Henderson, had begun to question and to delve into the true origins of the game.

Henderson found, and described in his book Ball, Bat and Bishop: The Origin of Ball Games (U Illinois Press 1947), that games involving a stick and a ball had been played in cultures throughout the world since ancient times. Further, he showed that a game called ‘stoolball’ – involving a ball, bat and stumps or bases – had been played in England for some 600 years! And that it is a version of this game that is “a direct forbear” of baseball. More significantly however, he found earlier references to baseball that even the meticulous compilers of the Oxford English Dictionary had missed: that the ‘first’ [it is not — see below] actual mention of ‘baseball’ occurs in 1744 [or 1748 — again, see below] in a letter of Lady Hervey in which she writes about the habits and pastimes of Frederick, the then Prince of Wales: “The Prince’s family divert themselves at baseball, a play all who are, or have been, schoolboys are well acquainted with.” No less telling than the actual mention of ‘baseball’ is that Lady Hervey implies that the game was well known and had been played for some time in England [again — see below].

Also in 1744, the children’s book A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, Intended for the Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly, to give its full title, was published in London. It was one of the first books published for ‘juvenile amusement’, and as well as the predictable games of cricket and taws (marbles) is B for ‘base-ball’.

Yet there still seems to be a general ignorance of, or at least misconception about, the game in England. Despite the association of baseball with America, for 200 years literally myriads of readers would have read Jane Austen’s mention of baseball in 1803 – and promptly forgotten it. Introducing her heroine Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey, Austen says in her third paragraph that Catherine “should prefer cricket, base ball, riding on horse back, and running about the country, at the age of fourteen, to books …”. Nevertheless, Austen’s mention reinforces what Henderson had discovered. There is a huge literature about baseball and its history, and several famous writers have given us popular summaries, including no less than Alastair Cooke, the children’s book historians Peter and Fiona Opie, and Bill Bryson.

It is in the Opies’ book Children’s Games in Street and Playground (OUP 1969) that A Little Pretty Pocket-Book is described. And Alastair Cooke in Talk About America 1951–1968 (Penguin Books 1968) mentions Lady Hervey’s letter, “a children’s book of games” (clearly meaning the Little Pretty Pocket-Book) and summarizes Henderson’s research. In Made in America (Secker & Warburger 1994) the indefatigable researcher Bryson, in addition, tells us that there is “mention of a bat in the context of American play … in 1734”; that ‘The Boston Massacre’ (1770) that helped propel the American colonists into eventual revolution “was provoked in part by someone waving a tipcat bat in a threatening manner at the British troops”; and that “soldiers at Valley Forge are known to have passed the time in 1778 by ‘playing at base’”.

Yet we still find a statement such as the following at the beginning of no less a compendium than The Baseball Encyclopedia (1988 edition). Describing the now famous first organized game between the Knickerbockers and the New York Nine on the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey on 19 June 1846 – “under rules established by one Alexander J. Cartwright” – it is declared unequivocally that this game “served to mark the only acceptable date of baseball’s beginning”. It is the guarded “under rules established by…” that qualifies the statement — for it is axiomatically untrue as baseball’s actual beginning.

Irrespective of the dates of the publications cited above, there was a stir of excitement in spring 2007 when a diary for the years 1754–1755 by one William Bray of Shere, Surrey was found ‘in a garden shed’. In his entry for Easter Monday 31 March 1755 Bray describes how after church and dinner he went “to Miss Jeale’s to play Base Ball” with several male and female friends. The discovery was featured on the BBC Today Programme and on several local southern news stations, both radio and TV, and subsequently nourished several newspaper articles as well. This has begun to foster another myth, or shall we say misconception: that baseball ‘started’, or at least was first mentioned, in Shere, Surrey in 1755. Statements occurred – even as recently as 2010 – such as, “The first reference to baseball in the world [my emphasis] occurs in the diary of a Surrey solicitor, William Bray, in 1755”, in ‘It’s not cricket, but baseball is making its mark on our game’ by Scyld Berry in The Telegraph (16 July 2010).

This last claim is categorically untrue, for what all the authors cited above seem to have missed is the telling statement that was always there in Henderson’s book in 1947: “The earliest mention of the game called baseball so far located was made by the Reverend Thomas Wilson, a Puritan divine at Maidstone, England. He wrote reminiscently in the year 1700, describing events that had taken place before that time, perhaps during his former years as a minister. ‘I have seen,’ he records with disapproval, ‘Morris-dancing, cudgel-playing, baseball and crickets, and many other sports on the Lord’s Day.’”

I also think another recent ‘discovery’ makes a claim that seems a little shakey — David Block of SABR (Society for American Baseball Research), ‘New discovery by SABR member David Block confirms that baseball was played by royalty in England in 1700s’ (although, please note, the actual author of this website article is not categorically stated to be David Block). In this article it is claimed that Block’s discovery of an article in The Whitehall Evening Post for 19 September 1749 “overturns their [baseball historians’] assumption that it [baseball] was played only by children and young adults”. Here’s the full text in the website article cited above:

“A prominent member of the British royal family played baseball more than 250 years ago. This is according to the latest discovery of SABR member and author David Block, who specialises in the study of baseball’s origins.

Combing through an obscure 1749 newspaper, Block spotted the following news item: “On Tuesday last, his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, and Lord Middlesex, played at Bass-Ball (sic), at Walton in Surry (sic); notwithstanding the Weather was extreme (sic) bad, they continued playing several Hours.”

Though Block and other baseball historians have long been aware that the game originated in Britain before migrating to the North American colonies, this discovery overturns their assumption that it was played only by children and young adults. Frederick, the Prince of Wales, and his playing partner Charles Sackville, (1711–1769), Earl of Middlesex were not only members of the aristocracy, but also men entering their early middle age.

On what basis is this claim made that baseball historians ‘assumed’ that the game was only played by children and young adults? Surely, by now, they all know about Lady Hervey’s letter. And, on what basis rests the implication that the 1749 Whitehall Evening Post article is the earliest mention of aristocracy playing baseball?

Henderson dates the letter by Lady Hervey as November 14, 1748 (Henderson 1947, 2001, page 134); for reasons unknown to me, Alastair Cooke, in summarizing Henderson’s research, states that Hervey’s letter is dated 1744 (Cooke 1968, page 47). Block [or whoever] himself says (in the website article cited above) that the 1749 article is “not the first time Frederick’s [Prince of Wales] name has been associated with the game”, and refers to the Lady Hervey letter, dating it 1748. However, delving deeper, Block has found “a handwritten copy of Lady Hervey’s letter, probably made later [than 1748] in the 18th century, in an archive in Suffolk, England, and her collected letters, including the one mentioning baseball, were published in 1821” [that is, ‘not published until 1821’]. Also, “An even earlier reference to baseball probably appeared in a children’s book, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, that was first published in 1744. However, the earliest known surviving copy of that book is a 1760 edition in the British Library.” Perhaps the 1744 first publication of A Little Pretty Pocket-Book is what confused Alastair Cooke?

Nevertheless, in the interests of accuracy, it still needs to be explained why the fact that these two references earlier than 1749, whose surviving publication copies are 1760 and 1821, makes their earlier dates of being written somehow questionable. They still constitute two known references to baseball originally made in 1744 and 1748. Where do the 1744 and 1748 dates come from if not in the later copies, and from the original documents from which the surviving copies were made?

Modern and 18th Centry Teams with Handa Bray

But there we have it. Despite getting their dates a little mixed, and missing, or at least ignoring, some references and selecting others, all these writers, and many more, show conclusively that a game called baseball was played in southern England in the 18th century and earlier. The game was obviously not exactly the same as the game played today, and the rules, as they now stand, are clearly the American contribution of the 19th and 20th centuries.

We can be proud that baseball was a popular pastime in Surrey and Kent in the 18th century. Baseball is still played extensively in England, especially on an amateur basis. Perpetuating this history, the Guildford Baseball Association [from 2014, Guildford Baseball and Softball Association] is proud to ‘play ball’ in ‘the home of baseball’ and we continue our efforts to extol and spread the game as ‘The Guildford Mavericks’.

On 19 June 2011 Surrey County Council invited us all to Surrey’s Sporting Life 2011: Celebrating Surrey’s Rich Sporting Heritage at the Surrey Sports Park in the University of Surrey to re-enact a version of that Shere baseball game of 1755. We were delighted to do so and carry on the tradition! The BBC were in attendance and created this short video – Baseball’s birth place marked by the people of Surrey

Those wishing to read fuller descriptions of baseball’s early development, see chapters ‘21 Baseball: Infancy’ and ‘22 Baseball: Adolescence’ in Henderson’s 1947 book — reprinted 2001, also by U Illinois Press; David Block’s book Baseball Before We Knew It (U Nebraska Press 2005); and, more recently, Bill Bryson’s One Summer: America 1927 (Transworld Publishers 2013, chapters 8 and 9.

* This is an adapted and extended version of an original article written for and published in the Surrey community magazine Round and About in October 2011.

© David M. Jones 28 June 2014

Click here for more pictures of the Guildford Mavericks reenactment in Shere

No comments yet.